What If: Ditching Social Security Numbers for Personal ID Keys

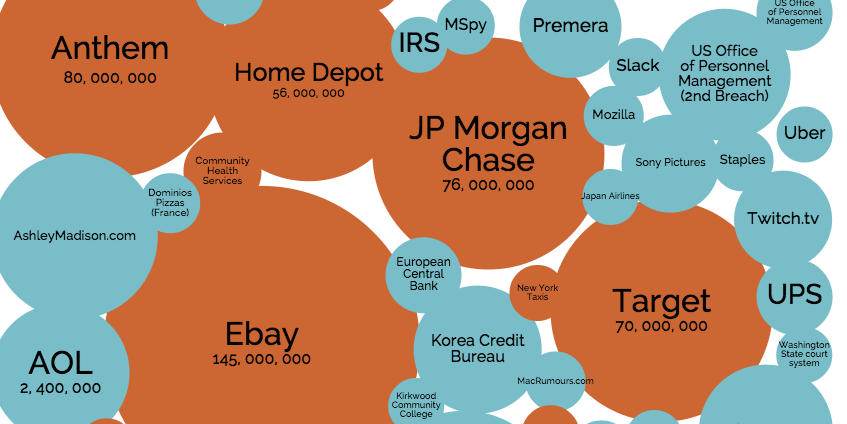

I’ve been thinking about this discussion on a National ID and the end of using Social Security Numbers. We’re used to having these 9 digit numbers represent us for loans, credit card transactions, etc., but in the modern age one would think we could do better.

Any replacement for Social Security Numbers would need to be secure, reduce the chances of identity theft, be able to withstand fraud/theft, and must not be scannable without knowledge (to avoid being able to track a person without their knowledge as they go from place to place). The ACLU has a list of 5 problems with National ID cards, which I largely agree with (though some — namely the database of all Americans — already exist in some forms (SSN, DMV, Facebook) and are probably inevitable).

In an ideal world, we’d have a solution in place that offered a degree of security, and there are technical ways we could accomplish this. The problem with technical solutions is that not every person would necessarily benefit (there are still plenty of Americans without easy access to computers), and technical solutions leading to complexity for many. However, generations are getting more technically comfortable (maybe not literate, but at least accustomed to being around smartphones and gadgets), and it should be possible to design solutions that require zero technical expertise, so let’s imagine what could be for a moment.

Personal ID Keys

Every year we have to renew our registration on our cars, and every so many years we have to renew our drivers license cards. So we’re used to that sort of a thing. What if we had just one more thing to renew, a Personal ID Key that went on our physical keychain, next to the car keys. Not an ID number to remember or a card that can be read by any passing security guard or police officer or device with a RFID scanner, but a single physical key with a safe, private crypto key inside, a USB port on the outside, that’s always with us.

I’m thinking something like a Yubikey, a simple physical key without any identifiable information on the outside that can always be carried with you. It would have one USB port on the outside and a single button (more on this in a minute). You’d receive one along with a PIN. People already have to remember PINs for bank accounts and mobile phones, so it’s a familiar concept.

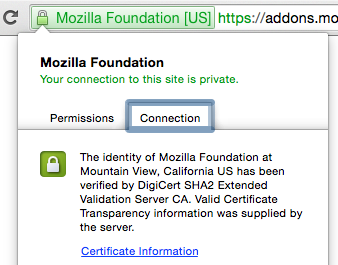

Under the hood, this might be based around PGP or a similar private/public key cryptography system, but for the purpose of this “What if,” we’re going to leave that as an implementation detail and focus on the user experience. (Though an advantage of using PGP is that a central government database of all keys is not needed for all this to work.)

When you receive your Personal ID Key and your PIN (which could be changed through your computer, DMV, or some other place), it’s all set up for you, ready to be used. So how is it used? What benefits does this really give? Well, there’s a few I can think of.

Signing Documents

When applying for a home loan or credit card agreement, or when otherwise digitally signing a contract online, you’d use your Personal ID Key. Simply place it in the USB port and press the activation button on the key. You’ll have a short period of time to type your PIN on the screen. That’s it, you’re done. A digital signature is attached to the document, identifying you, the date, and the time. That can be verified later, and can’t be impersonated by anyone else, whether by a malicious employee in the company or a hacker half-way across the world.

Replacing Passwords

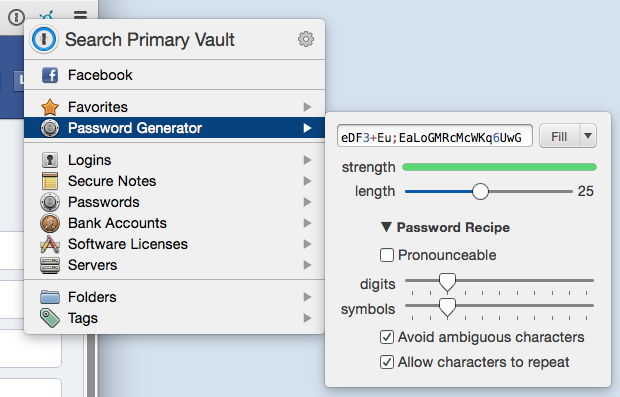

People are terrible when it comes to passwords. They’ll use their birthdates or their pet’s name on their computer and every site on the Internet. More technical people try to solve this with password management products, but good luck getting the average person to do this. I’ve tried.

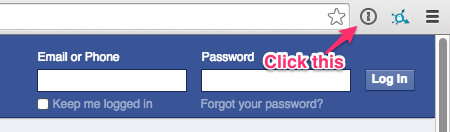

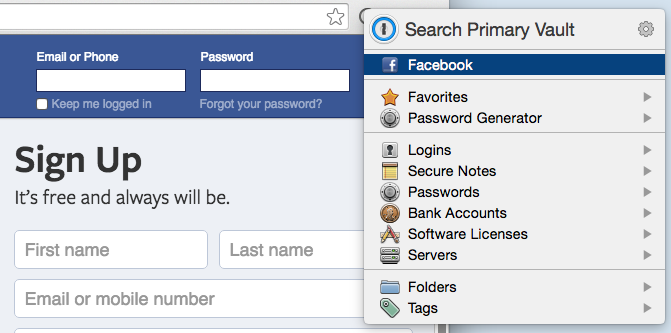

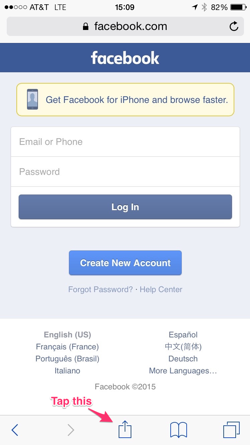

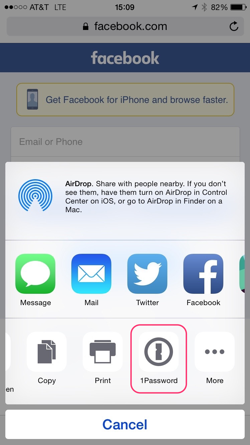

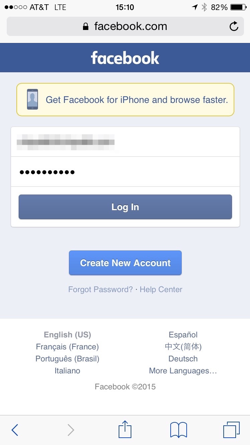

This can be largely addressed with a Personal ID Key and the necessary browser infrastructure. Imagine logging into your GMail account by typing your username, placing your key in the USB port on any computer, pressing the activation button, and typing your PIN. No simple passwords that can be cracked, and no complex passwords that you’d have to write down somewhere. No passwords!

Actually, for some sites, this is possible today with Yubikeys (to some degree). Modern browsers and sites supporting a standard called U2F (such as any service by Google) allow the usage of keys like this to help authenticate you securely into accounts. It’s wonderful, and it should be everywhere. Granted, in these cases they’re used as a form of two-factor authentication, instead of as a replacement for a password. However, server administrators using Yubikeys can set things up to log into remote servers using nothing but the key and a PIN, and this is the model I’d envision for websites of the future. It’s safe, it’s secure, it’s easy.

Replacing the Key If Things Go Wrong

Inevitably, someone’s going to lose their key, and that’s bad. You don’t want someone else to have access to it, especially if they can guess your PIN. So there needs to be a process for replacing your key at a place like the DMV. This is just one idea of how this would work:

Immediately upon discovering your key is gone, you can go online or call a toll-free number to indicate your key is lost. This would lead to an appointment at the DMV (or some other place) to get a new key, but in the meantime your old key would be flagged as lost, which would prevent documents from being signed and prevent logging into systems.

Marking your key as lost would give you a special, lengthy, time-limited PIN that could be used to re-activate your key (in case you found out you left it in your other pants).

The owner of the key would need to arrive at the DMV (or wherever) and prove they are who they say they are and fill out a form for a new key. This would result in a new private key, and would require going through a recovery process for any online accounts. It’s important here that another person cannot pretend to be someone else and claim a new key.

Once officially requested at the DMV, the old key would be revoked and could no longer be used for anything.

Replacing the Key If Standards Change

Technology changes, and a Personal ID Key inevitably will be out-of-date. We’ve gone through this with credit cards, though. Every so often, the credit card company will send out a new card with new information, and sites would have to be updated. Personal ID Keys wouldn’t have to be much different. Get a new one in the mail, and go through converting your accounts. Sites would need to know about the new key, so there’d need to be a key replacement process, but that’s doable.

Back to Reality

This all could work, but in reality we have infrastructure problems. I don’t mean standards support in browsers or websites. That’s all fixable. I mean the processes by which people actually apply for loans, open bank accounts, etc. These are all still very heavily paper-based, and there’s not always going to be a USB port to plug into.

Standards on tablets and phones (in terms of port connectors and capabilities) would have to be worked out. iPads and iPhones currently use Lightning, whereas most phones use a form of USB. Who knows, in a year even Apple’s devices might be on USB 3, but then we’re still dealing with different types of USB ports across the market, with no idea what a future USB 4 or 5 would look like. So this complicates matters.

Some of this will surely evolve. Just as Square made it easy for anyone to start accepting credit card payments, someone will build a device that makes it trivial to accept and verify signatures, portably. If the country moved to a Personal ID Key, and there was demand for supporting, devices would adapt. Software and services would adapt.

What If: Ditching Social Security Numbers for Personal ID Keys Read More »