Django’s a powerful toolkit and offers many things to ease the creation of websites and web applications. Features such as the automatically built Administration UI are just awesome and save developers from having to reinvent the wheel on every project. It does fall short in a few areas, however, and one of them is site configuration.

Now, Django’s settings support isn’t bad. You get a nice little settings.py file to put settings in for your site/webapp, and since it’s just a Python module, your settings can really hold whatever data you want and can be well documented with comments. That’s all great, but when you want to actually change a setting, you must SSH in, edit the file, save it, and restart the server.

This is fine for small websites with a few visitors, or sites with almost no custom settings, but for large sites it can be a problem. Bringing down the site however briefly could interrupt users, generate errors, causing worries during a checkout process or when editing a post on a site. Doing anything more complex and preventing downtime really means rolling your own thing.

So we rolled our own thing. Review Board has operated with the standard Django settings module since day 1, but it’s become obvious over time that it wasn’t good enough for us. So we wrote the dynamic Site Configuration app for Djblets.

djblets.siteconfig

siteconfig is a relatively small Django app that stores setting data in the database, along with project versioning data in case you need it to handle migrations of some sort down the road. There’s a lot of useful things in this app, so I’ll summarize what it provides before I jump into details:

-

Saving/Retrieving settings.

Setting values can be simple strings, integers, booleans, or something more complex like an array of dictionaries of key/value pairs.

-

Default values for settings.

These default values could be provided by your application directory or could be based off the contents in your settings.py file.

-

Syncing to/from settings.py.

Just because you’re using djblets.siteconfig doesn’t mean you can’t still support settings.py. Settings can be pulled from your old settings and saved back there when modified.

-

Compatibility with standard Django settings.

Django offers a lot of useful settings that you may want to customize. We do the hard work of mapping these and keeping them in sync so you can customize them dynamically.

-

Auto-generated settings pages.

Much like the existing admin UI, we offer an easy way to provide settings pages for your application. Go ahead and stick these in the admin UI if you like.

Getting Started

To start out, you’ll want to add some code in your app that creates a SiteConfiguration model, perhaps as a post_syncdb management hook. This is project-specific, since you’ll be storing version information in here and linking it with your existing Site. Here’s one way to do it. We’ll use this file as a template in later examples:

# myapp/siteconfig.py

# NOTE: Import this file in your urls.py or some place before

# any code relying on settings is imported.

from django.contrib.sites.models import Site

from djblets.siteconfig.models import SiteConfiguration

def load_site_config():

"""Sets up the SiteConfiguration, provides defaults and syncs settings."""

try:

siteconfig = SiteConfiguration.objects.get_current()

except SiteConfiguration.DoesNotExist:

# Either warn or just create the thing. Depends on your app

siteconfig = SiteConfiguration(site=Site.objects.get_current(),

version="1.0")

# Code will go here for settings work in later examples.

load_site_config()

Saving/Retrieving Settings

Settings exist in a SiteConfiguration model inside a JSONField. Anything that Django’s native JSON serializer/deserializer code can handle, you can store. Usually you’ll want to store primitive values (strings, booleans, integers, etc.), but you’re free to do something more complex.

from djblets.siteconfig.models import SiteConfiguration

siteconfig = SiteConfiguration.objects.get_current()

siteconfig.set("mystring", "foobar")

siteconfig.set("mybool", True)

siteconfig.set("myarray", [1, 2, 3, 4])

mybool = siteconfig.get("mybool")

It’s pretty straightforward. The set/get functions are just simple accessors for the SiteConfiguration.settings JSON field, but you’ll want to use them because they’ll handle the registered defaults for settings, which I will get to in a moment.

Since this is just a Djblets JSONField, which is a glorified dictionary, you can do a lot of things, such as iterate through the keys and values:

for key, value in siteconfig.settings:

print "%s: %s" % (key, value)

And so on. Let’s go a step further.

Default Values

Say you’re starting fresh and just created your SiteConfiguration instance, or you’ve introduced a new setting into an existing site. The setting won’t be in the saved settings, so what value is returned when you do a get call? Well, that depends on your setup a bit.

In the first case, with a fresh new setting:

>>> print siteconfig.get("mynewsetting")

None

Any setting without a default value and not in the saved settings will return None. Good ol’ reliable None.. If you want to make sure you return something sane at this specific callpoint, you can specify a default value in the call to get, like so:

>>> print siteconfig.get("mynewsetting", default=123)

123

This can be really useful at times, but it’s a pain to have to do this in every call and keep the values in sync. So we provide a third option: Registered default values.

# myapp/siteconfig.py

defaults = {

'mystring': 'Foobar',

'mybool': False,

'mynewsetting': 123,

}

def load_site_config():

...

if not siteconfig.get_defaults():

siteconfig.add_defaults(defaults)

That’s all it takes. Now calling get with just the setting name will return the default value, if the setting hasn’t been saved in the database.

Down the road we’re going to have support for automatic querying of apps to grab their settings, giving third party apps an easier way to integrate into codebases using siteconfig.

Syncing Settings with settings.py

Django’s settings.py is and will continue to be an important place for some settings to go. If you’re developing a reusable application for other projects, you may not want to fully ditch settings.py. Or maybe you’re using a third party application that uses settings.py and want to make the settings dynamic.

siteconfig was designed from the beginning to handle syncing settings in both places. Now, when I say syncing, I don’t mean we write out to settings.py, since that would require enforcing certain permissions on the file. What we do instead is to load in the values from settings.py if not set in the siteconfig settings, and to write out to the settings object, an in-memory version of settings.py.

Let’s revisit our example above, but in this case we want to be able to dynamically control Django’s EMAIL_HOST setting.

# myapp/siteconfig.py

from django.conf import settings

from djblets.siteconfig.django_settings import apply_django_settings,

generate_defaults

settings_map = {

# siteconfig key settings.py key

'mail_host': 'EMAIL_HOST',

}

defaults = {

...

}

defaults.update(generate_defaults(settings_map))

def load_site_config():

...

apply_django_settings(siteconfig, settings_map)

What we did here was to generate a mapping table of our custom settings to Django settings.py settings. We can then generate a set of defaults using the generate_defaults function. This goes through the Django settings keys, pulls out the values if set in settings.py, and returns a dictionary similar to the one we wrote above. This guarantees that our default values will be what you have configured in settings.py, handling the first part of our synchronization.

The second part is handled through use of the apply_django_settings function. This will take a siteconfig and a settings map and write out all values that have actually changed. So if “mail_host” above is never modified, apply_django_settings won’t write it out to the database, allowing the default value to change without having to do anything too fancy.

Compatibility with Django’s Settings

The above example dealt with the settings.EMAIL_HOST setting, but in reality we won’t have to cover this at all. There’s a few other goodies in the django_settings module that handle all the Django settings for you.

First off is get_django_settings_map. You’ll rarely need to call this directly, but it returns a settings map for all the Django settings sites are likely to want to change.

Then there’s get_django_defaults, which you’ll want to either merge into your existing defaults table or add directly. We don’t do it for you because you may very well not care about these settings.

The third is one you just saw, apply_django_settings. In the above example, we passed in our settings map, but if you don’t specify one it will use get_django_settings_map.

Let’s take a look at how this works.

# myapp/siteconfig.py

from djblets.siteconfig.django_settings import apply_django_settings,

get_django_defaults

def load_site_config():

...

if not siteconfig.get_defaults():

siteconfig.add_defaults(defaults)

siteconfig.add_defaults(get_django_defaults())

apply_django_settings(siteconfig, settings_map)

apply_django_settings(siteconfig)

This is all it takes.

If you take a look at django_settings.py, you’ll notice that we don’t reuse the existing Django settings names and instead provide our own. This is an attempt to cleanly namespace the settings used. You’ll also notice that there’s several settings maps and defaults functions. This is so you can be more picky if you really want to.

Auto-generated Settings Pages

Oh, this is where it gets fun.

Dynamic settings are all well and good, but if you can’t set them through your browser, why bother?

We wanted to make sure that not only could these be modified through a browser, but that it was dead simple to put up pages for changing settings. All you have to do is add a URL mapping and one form per page.

The form doesn’t even need much more than fields.

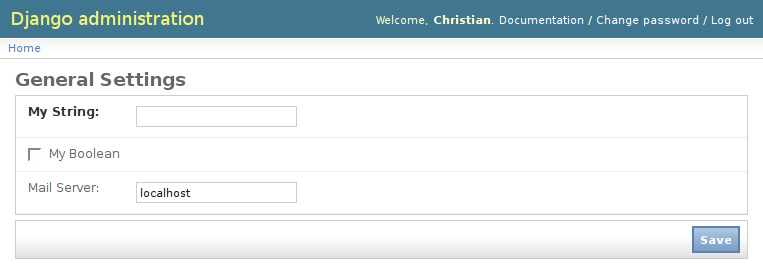

Let’s start out with some code. It should be pretty self-explanatory.

# urls.py

from myapp.forms import GeneralSettingsForm

urlpatterns = patterns('',

(r'^admin/settings/general/$', 'djblets.siteconfig.views.site_settings',

{'form_class': GeneralSettingsForm}),

(r'^admin/(.*)', admin.site.root),

)

# myapp/forms.py

from django import forms

from djblets.siteconfig.forms import SiteSettingsForm

class GeneralSettingsForm(SiteSettingsForm):

mystring = forms.CharField(

label="My String",

required=True)

mybool = forms.BooleanField(

label="My Boolean",

required=False)

mail_host = forms.CharField(

label="Mail Server",

required=False)

class Meta:

title = "General Settings"

That’s it. Now just go to /admin/settings/general/ and you’ll see your brand new settings form. It will auto-load existing or default settings and save modified settings. Like any standard form, it will handle help text, field validation and error generation.

Proxy Fields

For a lot of sites, this will be sufficient. For more complicated settings, we have a few more things we can do.

Let’s take the array above. Django’s forms doesn’t have any concept of array values, but we can fake it with custom load and save methods and a proxy field.

# myapp/forms.py

import re

class GeneralSettingsForm(SiteSettingsForm):

...

my_array = forms.CharField(

label="My Array",

required=False,

help_text="A comma-separated list of anything!")

def load(self):

self.fields['my_array'].initial =

', '.join(self.siteconfig.get('myarray'))

super(GeneralSettingsForm, self).load()

def save(self):

self.siteconfig.set('myarray',

re.split(r',s*', self.cleaned_data['my_array']))

super(GeneralSettingsForm, self).save()

class Meta:

save_blacklist = ('my_array',)

What we’re essentially doing here is to come up with a new field not in the settings database (notice “my_array” versus “myarray”) and to use this as a proxy for the real setting. We then handle the serialization/deserialization in the save and load methods.

When doing this, it’s very important to add the proxy field to the save_blacklist tuple in the Meta class so that the form doesn’t save your proxy field in the database!

Fieldsets

Much like Django’s own administration UI, the SiteSettingsForm allows for placing fields into custom fieldsets, allowing settings to be grouped together under a title and optional description. This is done by filling out the fieldsets variable in the Meta class, like so:

class GeneralSettingsForm(SiteSettingsForm):

class Meta:

fieldsets = (

{

'title': "General",

'classes': ('wide',),

'fields': ('mystring', 'mybool', 'my_array',),

},

{

'title': "E-Mail",

'description': "Some description of e-mail settings.",

'classes': ('wide',),

'fields': ('mail_host',),

},

)

This will result in two groups of settings, each with a title, and one with a description. The description can span multiple paragraphs by inserting newlines (“n“). All fields in the dictionary except for 'fields' are optional.

Re-applying Django settings

When you modify a field that corresponds to a setting in settings.py, you want to make sure you re-apply the setting or you could break something. This is pretty simple. Again override save as follows:

from myapp.siteconfig import load_site_config

class GeneralSettingsForm(SiteSettingsForm):

def save(self):

super(GeneralSettingsForm, self).save()

load_site_config()

This will re-synchronize the settings, making sure everything is correct. Note that down the road, this will likely be automatic.

There’s one last thing to show you…

Disabled Fields

Sometimes it’s handy to disable fields. Maybe a particular setting requires a third party module that isn’t installed. The SiteSettingsForm has two special dictionaries, disabled_fields and disabled_reasons, that handle this. Just override your load function again.

class GeneralSettingsForm(SiteSettingsForm):

def load(self):

if not myarray_supported():

self.disabled_fields['my_array'] = True

self.disabled_reasons['my_array'] =

"This cannot be modified because we don't support arrays today."

super(GeneralSettingsForm, self).load()

The resulting fields in the HTML will be disabled, and the error message will be displayed below the field.

Depending on whether or not you have a custom administration UI, you may want to tweak the CSS file or completely override it. Note that this all assumes that the djblets/media/ directory exists in your MEDIA_URL as the “djblets” directory. If you have something custom, you can always override siteconfig/settings.html and pass the new template to the view along with your settings form.

More Coming Soon!

There’s some new stuff in the works for the siteconfig app. Auto-detection of defaults and settings maps is the big one. I also have a few more useful tricks for doing advanced things with settings pages that I’ll demonstrate.

If you’re a user of Djblets, let us know, and feel free to blog about it! I’ll link periodically to other blogs talking about Djblets and projects using Djblets.

And as always, suggestions, constructive criticism and patches are always welcome 🙂